ELIZABETH RICE MATTISON, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Academic Programming and Curator of European Art

ASHLEY B. OFFILL, Curator of Collections

Hood Quarterly, spring 2024

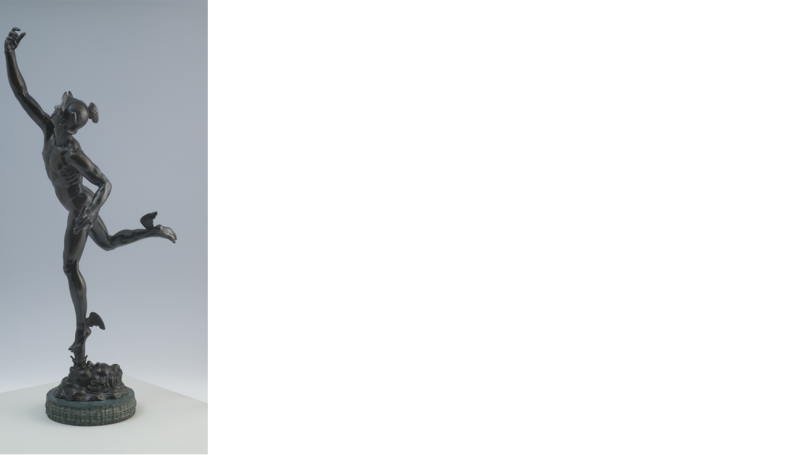

Sculpture surrounds us in our daily lives as fountains, monuments, and architecture. It is also in our homes, much as it was during the medieval period and the Renaissance. For example, the sculptor Giambologna (1529– 1628) created his Flying Mercury for a fountain to delight viewers in a dining hall or private garden (fig. 1). The exhibition Living with Sculpture: Presence and Power in Europe, 1400–1750 showcases the roles of sculpture in the houses, churches, and public spaces of Europeans in this period.

Recent examinations of sculpture suggest the singular presence and power that it holds for its makers, patrons, and audiences. The dynamism of sculpture became particularly evident in the 15th and 16th centuries with the explosion of interest in purchasing mass-produced objects such as plaquettes and small-scale bronzes. Innovations in the technology of making sculpture allowed artists to expand their markets and create new types of artworks.

Bringing together a variety of three- dimensional objects and related artworks, this exhibition demonstrates how makers and audiences exploited the engaging and tactile characteristics of bronze, wood, and stone. Whether given as tokens of affection, cast to memorialize events, designed to promote faith, or used in everyday life, these sculptures engaged their spectators in dialogues of devotion, authority, and intimacy. Among the most personal items were portrait medals. Featuring a face on one side and an allegorical or emblematic scene on the other, these objects became markers of identity. Celebrating the triumph of Gustavus Adolphus at the Battle of Brietenfeld near Leipzig in 1631, the Swedish king's portrait medal features his profile on the face and an allegory of justice and victory on the reverse (fig. 2). This medal was possibly given as a gift to soldiers for their valor in service to the ruler.

Individuals avidly collected medals as a way of materializing their social networks. Collectors gathered these objects in chests and drawers or hung them on the wall to publicize their connections to depicted rulers, allies, and even religious figures. In the exhibition, we recreate some of the bonds preserved and forged in medals. Installations reunite husbands and wives, fathers and sons, kings and vassals (fig. 3). The exhibition also features a collector's table, which evokes a space for artistic contemplation found in a 16th-century home. The placement of statuettes, plaquettes, and an inkwell in the galleries echoes the ways disparate objects would come together to promote their owner's intellect and status.

In addition to personal relationships, sculpture was a key part of religious experience. Churches were filled with carved altarpieces, statues of saints, reliefs of biblical narratives, and objects used in devotional practice. These sculptures were not passive occupants of this space; rather, they were activated through touch, smell, flickering candles, and sounds of religious ritual. A carved sculpture of a woman's head would have held a relic, a physical remainder of a saint, and offered a connection to her divine presence (fig. 4). Almost life-sized, painted with a sweet expression and bright colors, the saint seems to come alive.

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue featuring new research and photography of the Hood Museum's important collection. Many of these works have never been on display before; together, they attest to the central role that sculpture played in giving shape to the daily lives of people across social classes in Europe. See page 3 for more details.

Living with Sculpture and its corresponding catalogue are organized by the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, and generously supported by the Leon C. 1927, Charles L. 1955, and Andrew J. 1984 Greenebaum Fund, and by grants from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.