ASHLEY OFFILL, Curator of Collections

Hood Quarterly, winter 2024

Alchemists, practitioners of a proto-scientific tradition that had its origins in ancient philosophy, sought to transmute lead into gold. Scholars disagree regarding the nature of this change—is it a physical alteration of materials or an allegorical conversion of the spirit or the self? At its core, however, alchemy is the search to transform something of lesser value into something of greater value. Gold, gleaming and pure, held both monetary and symbolic worth for those alchemists, and for many other people and cultures throughout time. In Gilded: Contemporary Artists Explore Value and Worth, sixteen artists incorporate gold leaf into their paintings, sculptures, and installations in ways that, like alchemists of old, transform our material surroundings. However, their purposeful gilding pushes beyond an aesthetic choice to ask us, as we gaze at the shining surfaces: how do we decide what does and does not hold value?

The practice of gilding, or applying a thin sheet of gold leaf to a surface, has long held monetary value. In Il libro dell'arte, a 15th-century practical guide to artistic practice, the Florentine painter Cennino Cennini advises his readers to select gold leaf based on the number of sheets a gold-beater pounded from a single ducat. Ducats, gold coins used as currency throughout Europe between the 13th and 19th centuries, usually contained about three-and-a-half grams of nearly pure gold. Therefore, the shimmering gold that the artists applied to emphasize both saintly haloes and luxurious clothing could be measured based on its financial cost. However, a transformation seems to take place in the application of gold to a work of art, as metaphorical associations with morality, excellence, wealth, goodness, and brilliance carry the symbolic meaning of gold as a material beyond its value per ounce.

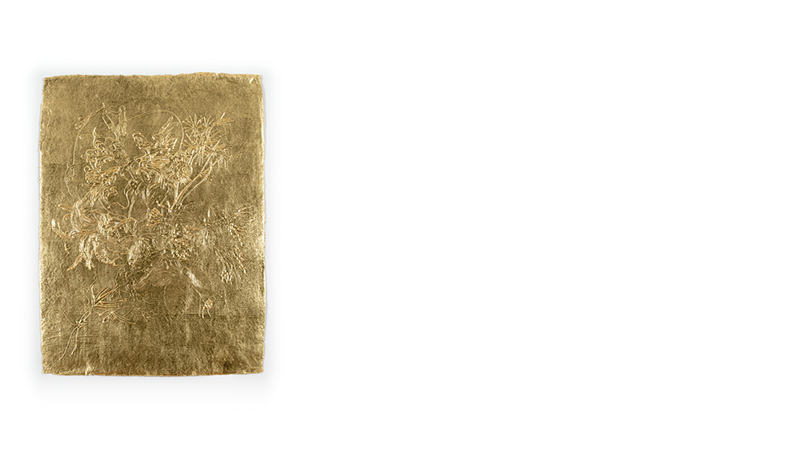

Stacy Lynn Waddell leans into these questions of value, both commercial and cultural, in her Floral Relief series. These works take inspiration from 17th-century Dutch floral still lifes, paintings which, despite appearing to have been painted from life, combine plants that grow in vastly different climates or flower in significantly different seasons. Rather than depicting truth, the original paintings celebrated global trade and the resulting wealth of the Dutch Republic without acknowledging the negative impacts of Dutch colonial ambitions. In each of the four works from her series included in Gilded, Waddell used an acrylic medium on handmade paper to outline a botanical scene before painstakingly layering and burnishing sheets of gold leaf to craft surfaces that are fragile, precious, and demanding, in that they require the viewer to physically move around to fully experience their varied textures. Waddell's choices capture the financial component of her source material but also encourage us to look more closely at what we value—are exotic flowers truly worth more than the human lives lost, through enslavement or otherwise, as a result of colonialism?

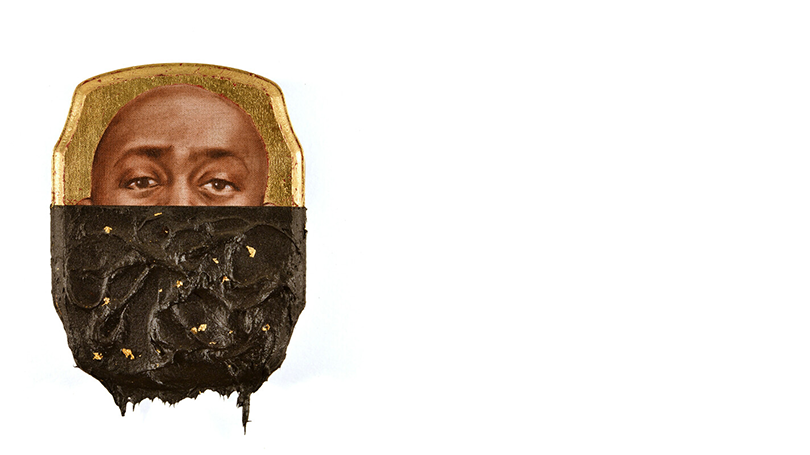

Titus Kaphar confronts the perceived value of individual lives in his Jerome Project. In these paintings, the face of a Black man gazes out from each gilded wooden panel, peering over a layer of thick black tar. Each of these men is named Jerome, and each one was incarcerated. Black men have a disproportionately high rate of incarceration; according to the ACLU, one in three Black men will go to prison during their lifetime, compared to one in 17 white men. Kaphar started the project after searching for information on his estranged father, named Jerome, which led to the discovery of ninety-nine Black men who shared Kaphar's father's name and who had also been arrested. The paintings feature the mugshots of the men placed against a golden background that evokes religious icons—objects of devotion that position holy figures as worthy of adoration. The tar, in contrast, obscures the men from view and, in many cases, covers their mouths. For the artist, the sticky tar visualizes the lingering aftereffects of imprisonment, which can often include the loss of the right to vote and other rights and freedoms even after the men are released. The undeniable allure of gold draws us into these works, while the glue-like tar pushes us to confront how imprisonment detracts from an individual's perceived worth.

The exhibition also features works by Radcliffe Bailey, Larissa Bates, william cordova, Angela Fraleigh, Gajin Fujita, Nicholas Galanin, Liz Glynn, Sherin Guirguis, Hung Liu, James Nares, Ronny Quevedo, Shinji Turner-Yamamoto, Danh Vo, and Summer Wheat. The Hood Museum of Art is delighted to host Gilded: Contemporary Artists Explore Value and Worth, which was curated by Emily Stamey at the Weatherspoon Museum of Art, University of North Carolina, Greensboro. Programming throughout the run of the exhibition will encourage visitors to investigate both the materials and techniques of gilding and the ways in which gold has been used across temporal and geographic boundaries as a way to indicate value and worth. Be sure to make time to visit the exhibition between February 3 and June 22 since, in the words of Dartmouth-favorite Robert Frost, "Nothing gold can stay."

Gilded: Contemporary Artists Explore Value and Worth is organized by the Hood Museum Art, Dartmouth, and is generously supported by the Ray Winfield Smith 1918 Memorial Fund.