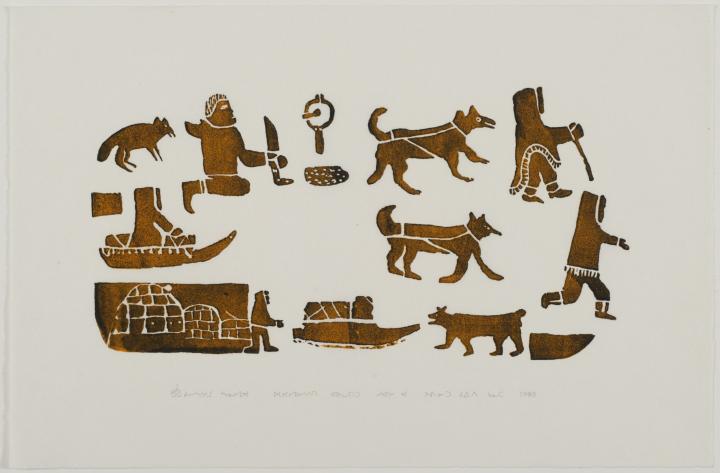

Sarah Joe Qinuajua, Ready to Leave for the Hunt, 1983, stonecut print on paper. Gift of Jane and Raphael Bernstein; 2011.64.17.

Based on the Learning to Look method created by the Hood Museum of Art. This discussion-based approach will introduce you and your students to the five steps involved in exploring a work of art: careful observation, analysis, research, interpretation, and critique.

HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE

1. Print out this document for yourself.

2. Read through it carefully as you look at the image of the work of art.

3. When you are ready to engage your class, project the image of the work of art on a screen in your classroom.

4. Use the questions provided below to lead the discussion.

Step 1. Close Observation

Ask students to look carefully and describe everything they see.

Start with broad, open-ended questions like:

* What do you see or notice when you look at this print?

* What else do you see?

Become more and more specific as you guide your students’ eyes around the work. Proceed row by row with questions such as:

* What do you notice about this figure? His pose?

* The clothing he is wearing?

* The objects and creatures nearby?

* What do you notice about this figure?

* Her pose?

* The clothing she is wearing?

* The object she is holding in her hand?

* What do you notice about this figure?

* His pose?

* The clothing he is wearing?

* The object he is sitting in?

* His size relative to the other figures?

* And finally this figure?

* His pose?

* The clothing he is wearing?

* What do you notice about the animals in this print?

* The modes of transportation?

* The shelter?

Finally, consider the arrangement of the figures and objects in this print.

* How would you describe this artist’s style? The shapes and forms of this print? The colors used?

Step 2. Preliminary Analysis

Once you have listed everything you can see about the object, begin asking simple analytic questions that will deepen your students' understanding of the work.

For instance:

* Where in the world might this scene take place? During what season? During what time period?

* Who are the various figures? What is their relationship to one another? What is their role within the family?

* What is the significance of the various animals? Can you identify them?

* What is the significance of the various tools?

* What kind of art form is this? Is it a scene of everyday life? A landscape? Both?

* What media do you think the artist is using?

After each response, always ask, “How do you know?” or “How can you tell?” so that students will look to the work of art for visual evidence to support their theories.

Step 3. Research

At the end of this document, you will find some background information on this object. Read it or paraphrase it for your students.

Now that your students have had a chance to look carefully and begin forming their own ideas about this work of art, feel free to share with them the background information at the end of this document. It provides information you cannot get simply by looking at this painting.

When you have finished sharing the information, consider the following:

* Does this information reinforce what you observed and deduced on your own?

* Did it mention anything you did not see or think about previously? If so, what?

* How would your experience of this print have been different if you had read the background information first?

Step 4. Interpretation

Interpretation involves bringing your close observation, preliminary analyses, and any additional information you have gathered about an art object together to try to understand what a work of art means. There are often no absolute right or wrong answers when interpreting a work of art. There are simply more thoughtful and better informed ones. Challenging your students to defend their interpretations based upon their visual analysis and their research is most important.

Some basic interpretation questions for this object might be:

* What does this print tell us about life in the Arctic? About winter hunting? About the roles of men, women, and children within an Inuit family?

* Why might an image like this appeal to a non-Inuit audience? What types of traditional knowledge does it celebrate and preserve for Inuit peoples?

Step 5. Critical Assessment and Response

Critical assessment and response involves a judgment about the success of a work of art. This step is optional but should always follow the first four steps of the Learning to Look method. Art critics often engage in this further analysis and support their opinions based on careful study of and research about the work of art.

Critical assessment involves questions of value. For instance:

* Do you think this print is well done? Why or why not?

* Do you think the artist effectively expressed her ideas and memories? Why or why not?

This fifth stage can also encompass one’s response to a work of art.

* Do you like this work of art? Does it speak to you in some way?

Background Information

Sarah Joe Qinuajua, Canadian Inuit, 1917–1986

Annie Amamatuak, Canadian Inuit, born 1933 (printmaker)

Ready to Leave for the Hunt, 1983

Stonecut print on paper

Gift of Jane and Raphael Bernstein; 2011.64.17

SARAH JOE QINUAJUA

Sarah Joe Qinuajua grew up in various hunting camps in northern Quebec and moved into the settlement of Puvurnituq in her early forties. Her subjects tend to be drawn from memories and experiences of her youth living on the land. The expression "on the land" is derived from the Inuktitut word nunamili, which refers to the seasonal migration of the Inuit as they followed the animals on which they depended for survival. Historically, Inuit people lived in camps and igloos on the ice in winter in search of fish, seals, walrus, and polar bear. They then moved inland into skin tents in the spring and summer to fish and hunt caribou. Living "on the land" also implies the Inuit practice of taking what they needed from nature: animals for food, their skins for shelter and clothing, and stone for tools and cooking pots.

This work recalls life at a winter camp. On the upper register, a kneeling male hunter holds a knife, used for cutting blocks of snow for an igloo and also for butchering animals. A fox and a fox or bear trap appear on either side of him. Below the trap is a seal breathing hole or a hole for ice fishing. To the right, a woman, wearing the traditional female parka known as an amauti, is shown walking ahead with a stick, checking the thickness of the ice. On the next level, a child is ferried on a komatik, or dogsled, while another child runs ahead. Harnessed dogs follow the mother and child. On the lower level, an igloo, Quinuajua's trademark, represents the family's winter camp. Nearby are another komatik, laden with items necessary for winter camping, and a polar bear. The isolated shapes on the field of white paper effectively communicate a sense of landscape, where figures appear silhouetted on the white ground of ice and snow.

HISTORY

During the mid-twentieth century, several changes occurred that pressured Inuit peoples to change their traditional life ways. Although largely self-sufficient, the Inuit had been engaged with the cash economy from the time explorers, whalers, and missionaries appeared on their shores. They acquired guns, seed beads, needles and thread, flour, tea, sugar, and other items on which they came to depend. Most trade relied on the Inuit ability to provide beaver and fox fur. In the 1930s, the Depression gripped Europe and America and demand for furs diminished. Without a means of acquiring cash to purchase rifles and ammunition, many families suffered periods of starvation and want.

In response to these events, the Canadian government became actively involved in the lives of the Inuit. In 1939, the Canadian Supreme Court accorded the Inuit and other First Nations of indigenous peoples the same rights and privileges to health, welfare, and education as all Canadians. The government issued family allowance checks, sent hospital ships to the Arctic, and a established program of low-cost housing in various settlements throughout the Arctic. Most importantly, the Canadian government required all Inuit children to attend school. Although the Inuit were not forced to move into settlements, most families were driven there by starvation, the need for medical treatment, and/or to be with their children.

Life in the settlements was extremely disorienting to a people used to hard work and independence. There was no way to provide a living for their families beyond the subsistence checks. Many medical providers, teachers, priests, and visiting artists (most notably the artist James Houston) recognized that the Inuit were practicing artists, skilled with their hands and profoundly knowledgeable about the land and animals of the Arctic. While the Inuit had been trading works they made out of a variety of materials since the time of contact, these visitors encouraged them to use their knowledge and skills to create work—in stone, fabric, and on paper—that would be oriented for a non-Inuit art market. The objects they produced are remarkable works of art, widely sought after by collectors, and now found in the collections of major museums all over the world. Most importantly, the production of this work created a vehicle for preserving cultural knowledge and sustaining tradition while innovating and creating new forms of expression.

PRINTMAKING

Sarah Joe Qinuajua was one of the first artists to produce material for the print shop in Puvirnituq. Although she was also a stone carver, she preferred creating drawings for prints. Printmaking was a new art form for Inuit peoples. Most of the print shops throughout the Arctic followed the practices of traditional Japanese printmaking—that is, the artists created the drawings and skilled Inuit printers produced the prints. Printmakers determined that stone was the best medium on which to work because it was readily available and Inuit peoples had been carving it for thousands of years.

The printmaker begins by copying the original drawing onto a flattened stone block. He or she chips away the unnecessary stone, leaving a raised surface upon which colored inks are rolled with a special tool, called a brayer. Because the ink is applied to a raised surface, stonecut is known as "relief" printing. The printmaker then lays a sheet of thin paper on the inked block and rubs the back of the paper by hand. After the ink has soaked into the paper, the paper is peeled from the stone block to reveal a sharp printed impression. The image appears in reverse of the original drawing.

Inuit printmakers make decisions about the size of the image and its placement on the stone. This work, printed by Annie Amamatuak, demonstrates the custom of printmakers from Puvurnituq of using the outline of the stone as a kind of frame. Its edges can be seen in the lower register of the print in the shape surrounding the igloo on the left and the curved, pointed shape on the right.