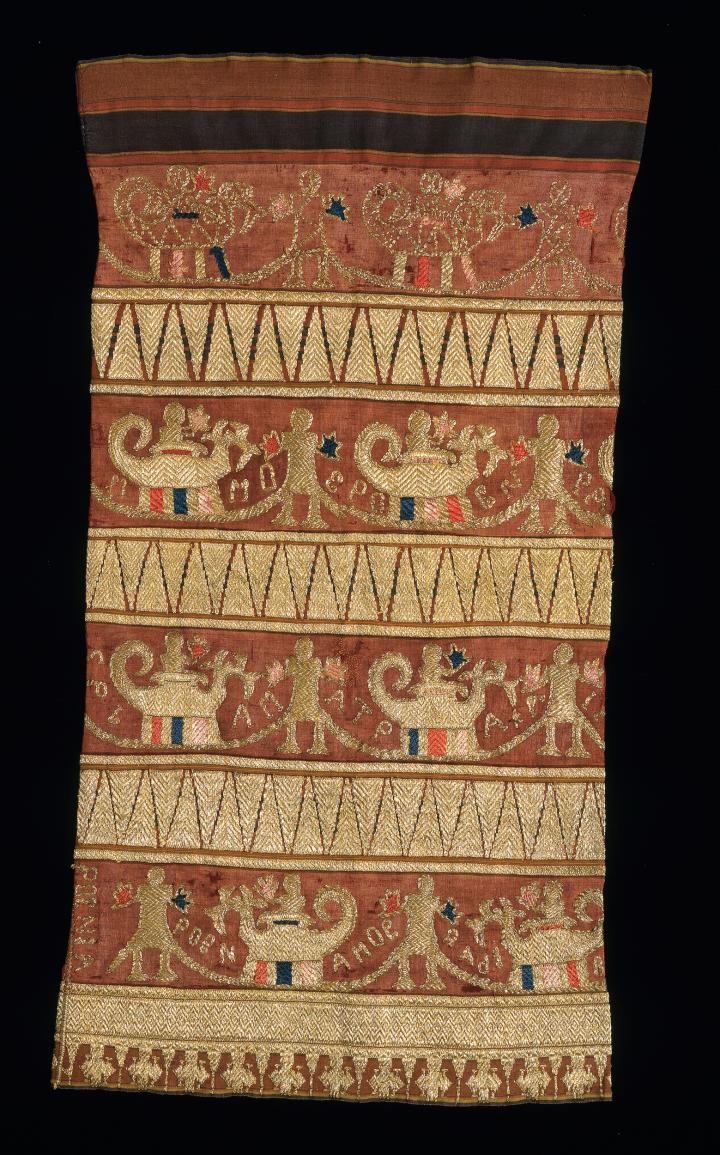

Unknown artist, Lampung Province, Sumatra, Indonesia, Tapis Raja Medal, woven in cotton, embellished with gold-wrapped thread. Lister Family Collection. Photo © 2004 by John Bigelow Taylor.

Based on the Learning to Look method created by the Hood Museum of Art. This discussion-based approach will introduce you and your students to the five steps involved in exploring a work of art: careful observation, analysis, research, interpretation, and critique.

HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE

1. Print out this document for yourself.

2. Read through it carefully as you look at the image of the work of art.

3. When you are ready to engage your class, project the image of the work of art on a screen in your classroom.

4. Use the questions provided below to lead the discussion.

INTRODUCTION

Explain to students that a tapis (pronounced tah-PEACE) is a type of textile created and worn by wealthy women in Lampung province on the island of Sumatra in the Republic of Indonesia. (See map at the end of this document.) Tapis are made by sewing together long strips of handwoven cloth to form a large rectangle. This cloth is decorated and then sewn into a tube. Women wear tapis for important events and ceremonies along with headdresses, gold jewelry, and additional wraps and scarves.

Tapis were extremely valuable, in part because the materials that decorate them (gold-wrapped thread, silk floss, and mirrors) were forms of currency. By wearing a tapis, a woman was literally wearing her family's wealth. Women have worn tapis in Lampung province for hundreds of years and still wear them today.

Step 1. Close Observation

Ask students to look carefully and describe everything they see. Start with broad, open-ended questions like:

* What do you notice about this tapis?

* What else do you see?

Become more and more specific as you guide your students’ eyes around the work with questions like these:

What do you notice about:

* the shape of this tapis?

* the colors used?

* the shapes and patterns?

* the way the patterns are arranged?

Step 2. Preliminary Analysis

Once you have listed everything you can see about the object, begin asking simple analytic questions that will deepen your students' understanding of the work.

For instance:

* What do you think is going on in this tapis detail?

* What do each of the shapes seem to represent?

* How do you think the artists created these images and patterns on the tapis?

* What process and materials do you think they used?

After each response, always ask, “How do you know?” or “How can you tell?” so that students will look to the work for visual evidence to support their theories.

Step 3. Research

At the end of this document, you will find some background information on this object. Read it or paraphrase it for your students.

Step 4. Interpretation

Interpretation involves bringing your close observation, preliminary analyses, and any additional information you have gathered about an art object together to try to understand what a work of art means. There are often no absolute right or wrong answers when interpreting a work of art. There are simply more thoughtful and better informed ones. Challenging your students to defend their interpretations based upon their visual analysis and their research is most important.

Some basic interpretation questions for this object might be:

* What does this tapis communicate about the wealth of the woman who made it and her family?

* What does this tapis tell us about what is valued and prized in this culture?

* Why do you think women traditionally wore the family's wealth in this culture?

* What does this tradition tell us about women's roles in this part of the world?

* How are these cultural traditions and roles similar to or different from your own?

Step 5. Critical Assessment and Response

Critical assessment and response involves a judgment about the success of a work of art. This step optional but should always follow the first four steps of the Learning to Look method. Art critics often engage in this further analysis and support their opinions based on careful study of and research about the work of art.

Critical assessment involves questions of value. For instance:

* Were the artists who created this tapis skillful and successful at expressing their culture's values?

* Would this tapis have been valued in Lampung? Why or why not?

Another realm that this fifth stage can encompass is one’s response to a work of art. Different from assessment, the realm of response can be much more personal and subjective.

* How do you feel about this tapis? Do you like it?

* What do you think of the craftsmanship involved? Does it remind you of any traditions, ideas, or values in your own culture?

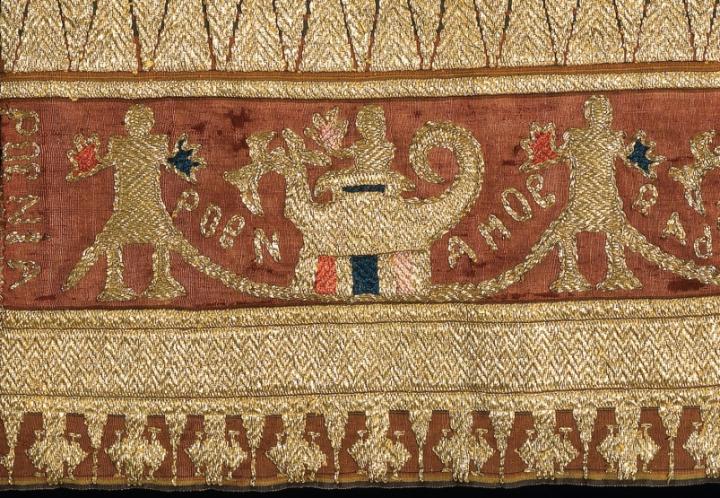

Detail A (left), detail B (right)

Background Information

Unknown artist, Lampung Province, Sumatra, Indonesia

Tapis Raja Medal

Woven in cotton, embellished with gold-wrapped thread

Lister Family Collection

Photo © 2004 by John Bigelow Taylor

Textile arts have been prized in Asia for hundreds of years. Along the so-called Silk Roads—over land and sea—textiles were traded as currency and commodities in the pre-modern world. On the large group of islands that make up the Indonesian archipelago, specially crafted textiles have played and continue to play significant roles in ceremonial events. They are used to wrap precious heirlooms, enclose or mark sacred spaces, and give visual prominence to important participants and leaders.

In the Lampung province of Indonesia's Sumatra Island, women have created elaborately worked tube-shaped sarongs called tapis. Tapis are constructed by sewing together strips of woven cloth and then decorating the large textile with a spectacular variety of ornamental materials. Although tapis may be worn by anyone today, this important personal adornment was once reserved for the prosperous nobility of the small "kingdoms" that established this region.

Ninth- and tenth-century records indicate that tapis were originally prestigious gifts for highly placed male leaders, but in the last several hundred years, tapis have been worn by women at ceremonies that celebrated marriages, coming-of-age rites, and the attainment of chiefly titles. The whole community observed these social achievements, highlighted by the spectacular displays of elite women adorned with ornate tapis, elaborate head-dresses, and masses of gold jewelry.

There is no evidence that tapis were worn to enhance or define a woman's body in previous centuries. Rather, women designed and decorated tapis in order to convey wealth, social station, and family affiliation; the woman's body was simply the vehicle of display.

Seagoing adventures and maritime commerce are dominant themes represented by a variety of motifs found in tapis. Lampung faces the Sunda Strait, which separates Indonesia's two best-known islands, Sumatra and Java, and is one of only two waterways through which ships can navigate between eastern and western Asia. As a result, the peoples of this province have enjoyed over two thousand years of maritime commercial connections with Asian and Middle Eastern empires and, more recently, Europeans and Americans. They traded pepper, elephants, gold, and other valuable commodities for prized textile goods and other items that could be used to embellish tapis, such as gold-wrapped thread and wire, silk floss, mica and mirrors, beads, metal sequins, and coins. (See detail A.)

As a result, throughout Southeast Asian coastal regions, wealth and status were symbolically intertwined with the concept of ships. In Lampung, tapis were the proof of a family's success and were often decorated with the ships that brought their wealth. In particular, naga-ships were important motifs. An ancient mythological creature, part serpent and part dragon, the naga figures into Lampung's early conceptualization of the world and the cosmos. Naga are associated with water, fertility, the moon, and the Milky Way; thus, successful transitions and voyages often were symbolized by naga.

This Tapis Raja Medal, or "King's Procession Tapis" illustrates a procession of naga-ships that alternate with figures facing the viewer—perhaps depicting an admiring audience. Lampung chiefs and their wives were conveyed to a ritual site in small palanquins, or wagons. The wagons took the form of dragon-headed boats with long, curling tails. (See detail B.) The procession of occupants seated "on deck" mimicked the important return of successful sailors. These images were created with gold-wrapped threads that were bent into shape and sewn onto the surface of the tapis with silk thread, a technique called "couching." The gold thread was too valuable to sew in and out of the fabric like traditional embroidery because half of the gold would have been hidden underneath.